SOURCE: AFI

India has recently signed a deal with GE Aerospace to supply LM2500 gas turbine engines, which will be assembled locally by Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) and used to power future Indian Navy ships. While this deal marks a significant step toward enhancing the Navy’s capabilities and strengthening indigenous defense production, there has been notable outrage on social media surrounding this development. Some have raised concerns over India’s continued reliance on foreign companies, while others question why alternatives—especially Indian or European options—aren’t being prioritized.

This article explores why this outrage exists, the reliability and proven success of the LM2500 engines, the potential alternatives, and whether India’s decision to work with GE Aerospace is a strategic one.

The primary source of discontent is the perception that India is continuing to rely heavily on foreign defense technology. Many believe that instead of opting for foreign solutions, the country should focus on developing indigenous technologies or sourcing engines from friendly European nations.

With India pushing for self-reliance in defense production under the “Make in India” initiative, critics argue that this deal contradicts the idea of fostering true indigenization. Although the engines will be assembled in India, some believe that full-scale manufacturing or the development of indigenous alternatives would better align with India’s long-term strategic goals.

A section of the critics believes that India should explore alternative suppliers, particularly from European nations or emerging domestic options, rather than relying on the U.S. They question whether a deal with GE Aerospace is the only viable option or if the Indian Navy could have considered more diverse choices.

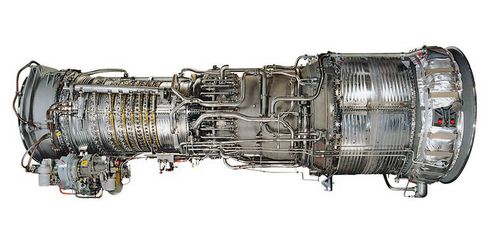

The LM2500 gas turbine engines have a well-established track record within the Indian Navy. Currently, they power several high-profile naval platforms like Shivalik-class frigates, Nilgiri-class frigates and also on the INS Vikrant, India’s first indigenous aircraft carrier.

The LM2500 has proven its reliability, efficiency, and durability in a variety of environments, including the challenging conditions faced at sea. Its design and performance have been continuously improved over decades, making it one of the most popular naval engines worldwide. More than 40 navies rely on the LM2500, demonstrating its global appeal.

In comparison, Zorya gas turbine engines from Ukraine, which were previously used by the Indian Navy on several ships, have faced issues related to reliability and support, especially amid the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. The LM2500, therefore, presents a more reliable and stable option, particularly in terms of long-term support and serviceability.

A crucial aspect of this new deal is that HAL will assemble the engines locally, which contributes to India’s goals of building up its defense manufacturing ecosystem. While the engines may not be fully produced in India, this agreement signals a step in the right direction, fostering local jobs, developing industrial capabilities, and advancing technology transfer.

The LM2500 is renowned for its high power-to-weight ratio, fuel efficiency, and ease of maintenance, qualities critical for naval vessels. The engine’s 30 MW (megawatts) power output is ideal for a wide range of naval platforms, from frigates to aircraft carriers. Until a proven and tested alternative is available domestically, opting for a less tested engine could jeopardize naval operations.

While some critics have argued that India should seek alternatives to the LM2500, both domestic and European options present certain limitations:

Kaveri Marine Engine (KMGT): India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) has been developing the Kaveri Marine Gas Turbine (KMGT) based on the Kaveri jet engine project. However, this engine is still in the development phase and has not yet been proven for large-scale use in naval vessels. While there is hope that this engine will eventually become a reliable option for the Indian Navy, it is not currently mature enough to replace the LM2500.

Indigenous Development Challenges: Developing a gas turbine engine from scratch is a complex and resource-intensive process, and it could take several more years for India to field an indigenous engine that meets the Navy’s power and efficiency requirements. Given the Navy’s immediate needs, relying solely on Indian options isn’t feasible at the moment.

European Alternatives

One alternative is the MT30 gas turbine from Rolls-Royce, which powers vessels like the British Royal Navy’s Type 26 frigates and the U.S. Navy’s Zumwalt-class destroyers. The MT30 offers 40 MW of power, making it more powerful than the LM2500. However, it is also more expensive and significantly larger, which may not suit the design constraints of future Indian Navy ships.

Another potential option is the Siemens SGT-500, but it is used primarily for industrial applications and lacks the extensive naval track record of the LM2500.

Both of these European alternatives, while technically capable, come with their own challenges in terms of size, integration complexity, and cost. Additionally, switching to a new engine supplier would require a reconfiguration of current platforms and infrastructure, adding further expense and complexity.

The outrage on social media, while reflecting legitimate concerns about India’s defense dependence, doesn’t fully account for the strategic and practical reasons behind the deal with GE Aerospace. The LM2500 engines have already proven themselves as reliable workhorses in the Indian Navy and globally, and the local assembly of these engines by HAL represents a significant step toward self-reliance.

At present, India lacks an indigenous or European alternative that offers the same level of power, efficiency, and proven reliability as the LM2500. Until domestic gas turbine engines like the Kaveri Marine Engine mature, partnering with foreign players like GE Aerospace, with an emphasis on local production and technology transfer, remains the most practical and strategically sound choice.