SOURCE: BLOOMBERG

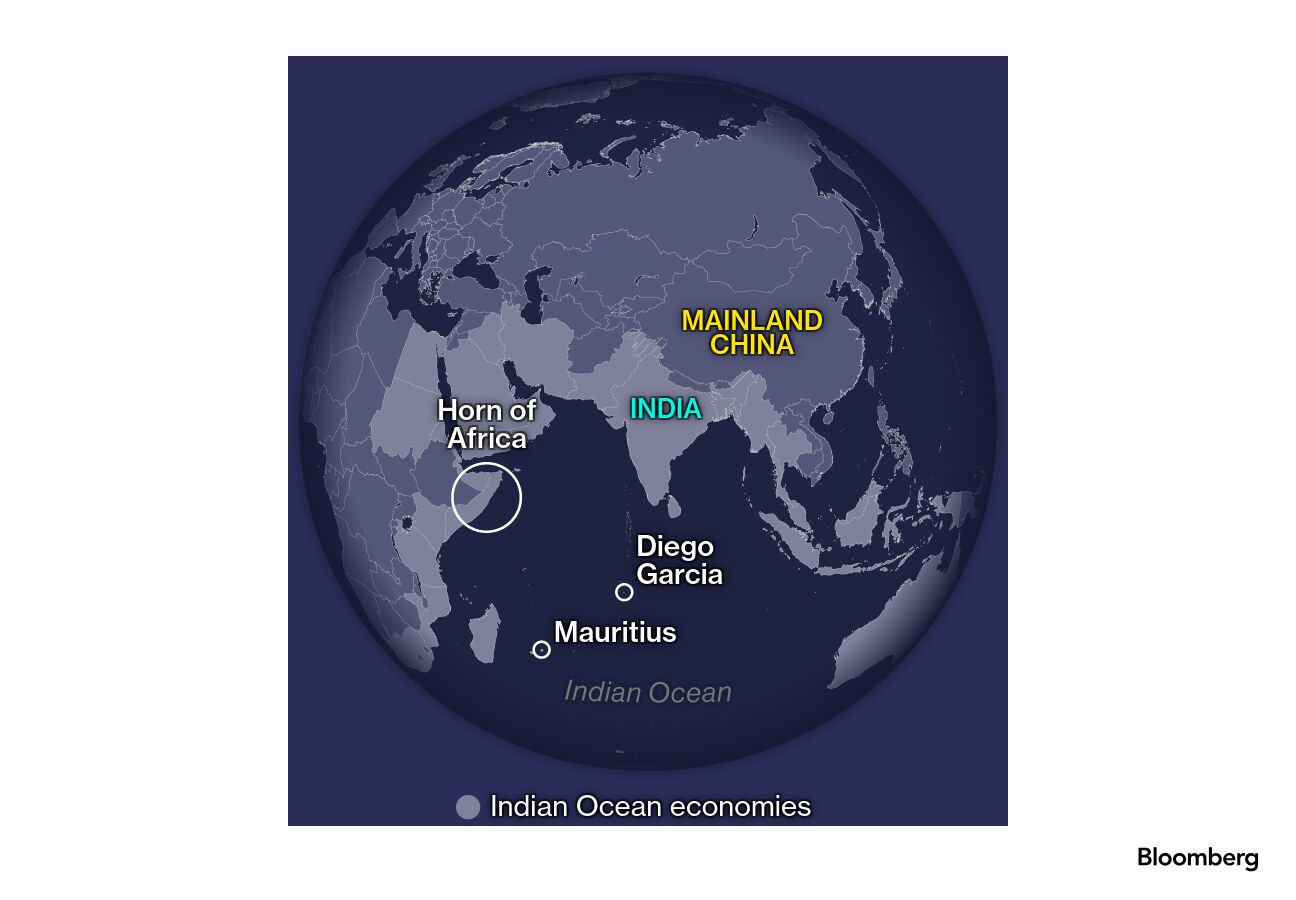

Diego Garcia, a remote Indian Ocean island nearly 2,000 miles from the East African coast, boasts clear-blue waters, pristine beaches — and a US-UK military base at the heart of the great-power chess match involving the US, China and India.

The British territory in the Chagos Archipelago – which has housed the base since the 1970s — is now at the center of a wider push by the US and India to counter China’s growing presence in the region. The Trump administration has said it’s inclined to support a deal reached by the UK last year to hand back the islands to Mauritius despite previous Republican concerns that the agreement could enable China to spy on US activities at the base.

While it’s largely flown under the radar, Diego Garcia, which sits near the center of the Indian Ocean, is arguably as important to American global strategic interests as Panama or Greenland, allowing the US to operate missions from the Middle East to Asia — and counter a growing Chinese presence in the region.

Over more than a decade, China has built up economic and military ties across the Indian Ocean, sending warships on training and anti-piracy missions while winning access to key naval bases. It has also poured billions into 46 commercial ports across the region, 36 of which are capable of hosting naval assets, according to data from the Council on Foreign Relations.

That has particularly alarmed India, which has constructed an airstrip where it can land surveillance aircraft on the Agaléga islands, another Mauritian territory some 1,100 miles west of Diego Garcia, in large part to track Chinese activity. This week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is the guest of honor at Mauritius National Day celebrations in the capital, Port Louis — part of an effort to reinforce the region’s importance to his country. New Delhi has also given its blessing to the Chagos deal.

“All these big powers are very much interested in the Indian Ocean, and the principal reason is because of the rise of Chinese power,” Dhananjay Ramful, Mauritius’ foreign minister, said in an interview from his office overlooking the harbor in the capital. “It’s all to do with geopolitics.”

India’s ministry of external affairs did not respond to an emailed request for comment. China’s foreign ministry said in a statement that all countries enjoy freedom of navigation in the Indian Ocean.

Stretching from the Horn of Africa to Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean is home to almost 3 billion people and around 40% of the planet’s offshore petroleum. Its waters include four of the world’s six most important maritime chokepoints and hold the key to trade between Europe, Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

Beijing has already made dramatic advances in the region.

China has constructed a military base in Djibouti and fostered a growing naval presence in Cambodia, giving it the potential to project power from both sides of the Indian Ocean. It regularly deploys destroyers, frigates and at least one submarine to conduct anti-piracy missions off Somalia. In the last year alone, Beijing has also penned a security pact with the Maldives and helped Pakistan launch stealth submarines.

Meanwhile, three dozen of the commercial ports China has built — from Mozambique to Australia — include berths deep enough for naval vessels, which has sparked concern in Washington.

While there’s no immediate flashpoint comparable to Taiwan or the South China Sea in the Pacific Ocean, India’s foreign minister and military officials have expressed alarm over the steady increase of China’s naval presence in the waters. With 95% of India’s trade and 80% of its crude oil supply flowing through the ocean, New Delhi sees unfettered access as a precondition for India’s rise.

Indian officials also say a Chinese-dominated Indian Ocean would leave them more vulnerable in any broader conflict with Beijing. In 2020, the two powers engaged in the deadliest clashes over their disputed Himalayan border since the two countries fought a war in 1962.

India’s Backyard

The US in recent years has sought to bring India further into its orbit in order to counter China. And while US President Donald Trump has threatened New Delhi with reciprocal tariffs, he also welcomed Prime Minister Narendra Modi to the White House last month as one of his first guests and pledged to deepen technology and defense ties, including with the sale of Lockheed Martin Corp.’s F-35 fighter jets to the South Asian nation.

“India should be taking the leading role in countering Chinese threats in the Indian Ocean region,” said Lisa Curtis, former senior director for South and Central Asia on the National Security Council during Trump’s first term. “The US wants India to be able to stand up to China, to compete effectively with China and to act as a counterbalance to China. It’s an important region.”

But India has faced setbacks, heightening its sense of vulnerability to Beijing. It failed to secure a military base in the Seychelles and has faced skepticism from new governments in the Maldives and Bangladesh.

“India finds itself on the back foot in what it sees as its backyard,” said David Brewster, author of India’s Ocean: The Story of India’s Bid for Regional Leadership. “They see themselves in the long-run as the leading natural power of the Indian Ocean and that makes them fragile to any expansion of Chinese influence.”

India’s struggles come down to its “big brother attitude toward its small neighbors,” said retired Chinese senior colonel Zhou Bo. “The traditional mentality is that this is India’s sphere of influence, but China got in” because of its desire to engage economically, he added.

Hanging over the competition is renewed uncertainty about the role of the US. While Trump has promised to compete with China, he’s also hostile to the kinds of overseas assistance that’s helped America gain influence in the region’s most strategic locations.

At the center of it all are tiny countries like Mauritius, which find themselves courted b“Now We Have a Choice”

Known for its azure seas and friendly tax regime, Mauritius lies some 700 miles east of Madagascar. The island nation is one of the wealthiest African countries and a mature democracy, and commands an exclusive economic zone larger in size than Greenland.

It’s also long been a focus of geopolitical competition. Britain took the island from France during the Napoleonic wars and used it to track Japan’s navy during World War II.

The US presence at Diego Garcia dates back to the 1960s, when India requested American military assistance in a war with China. The US signed a lease for the island from the UK — which detached the territory from Mauritius — and later used it to conduct strikes on Afghanistan and Iraq.

Now the main players are India and China, attested to by a flurry of construction across the country.

“We are being courted by a lot of people and we should use this to our advantage,” said Hans Nibshan Seesaghur, the former head of the Mauritius Economic Development Board office in Shanghai. “Now we have a choice.”

Indian companies are completing a new metro line connecting Port Louis to nearby cities. The project, reminiscent of Chinese infrastructure diplomacy, is part of a $353 million package that saw India build a new supreme court and hospital.

New Delhi’s history in Mauritius runs deep. Since independence in 1968, Mauritius’ national security adviser has always been an Indian national, as has its head of coast guard. Cultural ties are also significant: around two-thirds of its population are ethnically Indian.

Still, India has had to work to assert its influence amid a years’ long push by China.

In 2013, China completed work on a new international airport terminal, financed with a $260 million loan. In 2017, it completed the $108 million Bagatelle Dam, and has financed a $36 million sports complex and a $20 million cruise-ship terminal. In 2019, Mauritius became the first African nation to sign a Free Trade Agreement with China.

More concerning, US officials say, is the fact that Huawei Technologies Co. rolled out a surveillance camera system across the island.

Washington has also entered the fray, working with London to secure long-term access to the Diego Garcia base, which helps link its 5th fleet in Bahrain and its 7th fleet in Japan.

The US is also upgrading its embassy from a crowded space in an inauspicious office building into a $300 million compound outside the capital.

“Everything is playing to the advantage of Mauritius,” said Ramful, the foreign minister.

Chinese Funding

The same jockeying is playing out with Mauritius’ neighbors.

In Madagascar, China has built roads and hydroelectric power stations, and pledged to construct a special economic zone. In the tiny Comoros islands — where India and the US don’t even have embassies — China built a 10,000-seat stadium and has lavished it with high-level visits.

To the north, in the Seychelles, China is building a new headquarters for the Seychelles Broadcasting Corp. after constructing the country’s supreme court and national assembly. India tried and failed for years to secure a military base in the country despite its longstanding cooperation with the country’s coast guard. The US, prompted largely by China, reopened its embassy in June 2023 after a 27-year absence.

“We’re being wooed left, right and center,” said Ryan Adeline, a former Seychelles diplomat at the University of Seychelles.

More than 1,400 miles northwest of the Seychelles, the tiny African nation of Djibouti epitomizes US and Indian fears about Beijing’s inroads.

China opened its first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017, providing it a foothold on the Bab el-Mandeb strait — the gateway to the Red Sea crucial to oil exports from the Gulf. The US, France and others also have bases in Djibouti, but it’s China’s presence, so far from home, that speaks to its desire to secure sea lanes long policed by America.

Defense analysts say China’s current military footprint in the region would be vulnerable during wartime, but it’s the trend that worries US and Indian officials.

China is also looking for alternate footholds on Africa’s eastern seaboard, which has grown more significant since an upsurge in Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping has forced cargo around southern Africa. Washington believes Beijing is pushing for military port access in Tanzania and Mozambique, Bloomberg reported.

“From New Delhi’s perspective, this looks awful,” said Raja Mohan, an Indian strategic analyst at the National University of Singapore. “A stronger Chinese naval profile on the east coast of Africa will complement the PLA’s presence in Pakistan and base in Djibouti, allowing Beijing to dominate maritime choke points in the northwestern quadrant of the Indian Ocean.”

India Plays Catchup

Beijing’s growing clout has forced India to work harder to win hearts and minds closer to home in countries like Sri Lanka.

China poured $12.1 billion into infrastructure projects across the country between 2006 and 2019, according to Chatham House in London. Those investments included an enormous port in Hambantota, on which China secured a 99-year lease in 2017 as Sri Lanka struggled to pay its debts. In August 2022, a Chinese surveillance vessel docked at the port, prompting alarm in New Delhi.

Sri Lanka’s debts, combined with Covid’s impact on tourism and policy missteps, led the country to default on its sovereign debt in 2022. That crisis, though, created an opportunity for India, which issued a nearly $4 billion line of credit to the country, winning it plaudits from Sri Lankan elites.

“Because China invested, India upscaled their investment,” said Ali Sabry, Sri Lanka’s former foreign minister. “If we are smart enough we must use our strategic location to attract investment from China, India and the US.”

The country’s new president, political outsider Anura Kumara Dissanayake, has visited both India and China since taking office in September, securing promises of investment from both.

The picture is more problematic for India in the Maldives, where a pro-China candidate is now dominant, and in Bangladesh, which has become a significant concern since protesters overthrew the India-backed Sheikh Hasina.

As India seeks to win over officials in its neighborhood, it is also building military facilities. In addition to Agaléga, India commissioned a new base on its western seaboard on Minicoy Island last year and opened its first off-shore military logistics facility at the Duqm Port in Oman. Indian officials say they are also boosting military cooperation with France and Australia in the Indian Ocean as they look for partners to compete against Beijing.

Chinese Military Buildup

The competition continues more than 1,000 miles east of India’s southern tip at the entrance to the Malacca Strait, a chokepoint that Beijing worries America could use to block its energy supplies in a war over Taiwan.

India allowed the US access to its Andaman and Nicobar islands, which sit at the entrance to the strait, after joint exercises last year. It’s also posting troops there permanently for the first time.

Delhi meanwhile suspects China is building a surveillance post on Myanmar’s nearby Coco Islands, Indian officials say. The countries also have competing port projects in Myanmar’s restive Rakhine State, with India securing the rights to operate a port in Sittwe and China constructing a $7 billion deep-sea port at Kyaukphyu, which offers it a way to circumvent Malacca.

The boldest part of Beijing’s response to its Malacca dilemma lies in Cambodia, where the US says China has gained access to Ream naval base, where PLA Navy ships have made months-long visits, according to satellite imagery analyzed by the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Beijing and Phnom Penh deny such a deal exists. “I believe we have a need for some more,” Zhou, the former Chinese officer, said of Beijing’s quest for new bases. “Given China’s global interests, it is reasonable that there is a demand, but it won’t be easy.”

It’s possible, though, that Beijing’s momentum is slowing amid its economic malaise.

China is no longer able to spend like it did in the heady early years of its Belt and Road Initiative. Across the developing world, it has pivoted to lending at commercial rates on smaller projects.

The JinFei economic zone a few miles north of Port Louis shows how the old approach sometimes played out.

Launched with fanfare in 2009 as an area modeled on the economic zones that powered Chinese growth in the 1990s, the project aimed to bring $500 million of foreign investment into Mauritius within eight years and make Mauritius China’s gateway to Africa.

But inside its headquarters today, plaster hangs from the ceiling and signs in the elevator threaten tenants with lawsuits over unpaid rent. “Our company is currently facing financial challenges,” one sign says.

Over 300 of the zone’s original 500 acres have been reclaimed by the Mauritian government. Faded concept drawings on unused bus stops show a five-star hotel that never materialized. And a retail complex sits empty except for a shuttered hot pot restaurant.

Still, none of this means China has given up on the island — and the Mauritian government knows it.

Ramful, the foreign minister, said increased geopolitical competition makes it harder for great powers to ignore small countries like his.

“You shouldn’t take any country for granted,” he said. “There’s no exclusivity. We are open.”