SOURCE: AFI

A recently declassified document labeled “TOP SECRET,” covering the period from 1950 to 1959, offers a revealing glimpse into the geopolitical dynamics between India and China during a critical decade. The report, part of a historical analysis of India’s foreign policy under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, highlights the strategic missteps and ideological underpinnings that contributed to the deterioration of Sino-Indian relations, culminating in the 1962 border conflict. Titled “Section I (1950-1959) Summary,” the document sheds light on Nehru’s approach to China, his handling of the border dispute, and the broader implications for India’s national security.

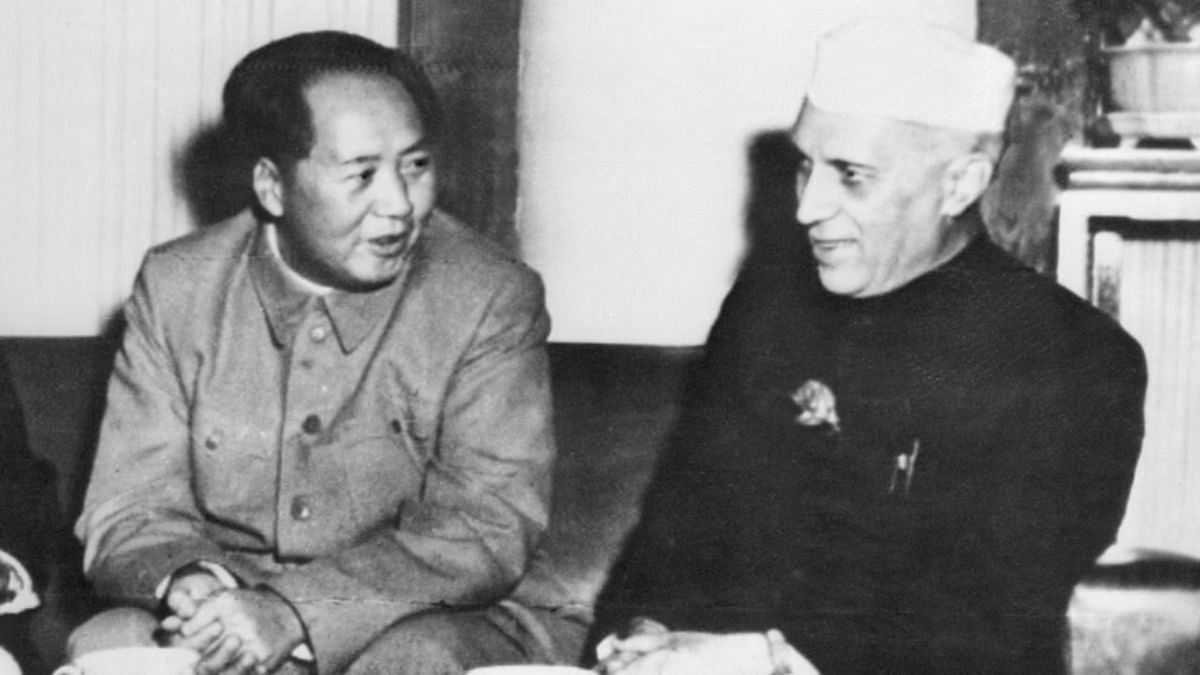

The document underscores a significant shift in Chinese military superiority between late 1950 and late 1959, a period marked by Mao Zedong’s consolidation of power and China’s growing assertiveness. During this time, Nehru adopted a policy of “friendship” toward the Chinese Communist regime, hoping to foster peaceful coexistence despite Beijing’s increasing hostility. The report notes that Nehru was “gentle” in his dealings with China, reflecting his belief in non-alignment and his vision of India and China as partners in a post-colonial Asian resurgence, often referred to as the “Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai” (India-China Brotherhood) era.

However, this approach proved futile as China pursued a “reckless” course in India’s border regions, particularly in the Aksai Chin area of Ladakh. The document reveals that Nehru was aware of China’s military buildup but chose to downplay the threat, believing that a strong Indian response would escalate tensions. Instead, he advocated for diplomatic solutions, calling for a “peaceful settlement” of the border issue—an approach the report describes as “irrelevant” given China’s lack of interest in negotiation.

The border dispute over Aksai Chin, a high-altitude plateau in Ladakh, is central to the document’s analysis. By the late 1950s, China had occupied the region, constructing a strategic highway linking Tibet and Xinjiang—a move India only protested through diplomatic notes and letters. The report highlights the “implicit defiance” in China’s actions, noting that Beijing did not formally occupy Aksai Chin but maintained effective control, a tactic that avoided outright confrontation while consolidating its territorial claims.

India, under Nehru’s leadership, failed to respond decisively. The document points out that India’s protests were “minor” and lacked the military or diplomatic weight to deter Chinese advances. Nehru’s reluctance to escalate the situation stemmed from his belief in the “strategic value” of Aksai Chin to China, which he saw as more significant than its value to India. However, the report argues that this view was a miscalculation, as Aksai Chin’s loss compromised India’s northern defenses and emboldened China to press further claims along the McMahon Line in the eastern sector (now Arunachal Pradesh).

The document also critiques Nehru’s broader foreign policy framework, noting his “overriding desire to acquiesce” in the face of Chinese expansionism. This stance was influenced by his ideological alignment with socialist principles and his admiration for China’s revolutionary model, despite Beijing’s clear hostility. Nehru’s approach contrasted sharply with the views of other Indian leaders, particularly those within the Congress Party, who favored a more assertive posture. The report suggests that domestic political dynamics, including pressure from the Congress Party and public opinion, eventually pushed Nehru to adopt a harder line—but by then, China’s military presence along the border had become entrenched.

One of the most striking revelations in the document is the differing perceptions of Aksai Chin’s strategic importance. Nehru viewed the region as more critical to China, particularly for its role in connecting Tibet and Xinjiang, and thus downplayed its significance to India. However, the report argues that Aksai Chin held “strategic value” for India as well, serving as a buffer zone against Chinese incursions into Ladakh and safeguarding India’s northern frontier. By ceding control to China without a fight, India lost a vital piece of territory, setting the stage for the 1962 war.

The document also notes that Aksai Chin’s strategic importance grew over time, as China leveraged its control to project power into Central Asia and assert dominance in the region. For India, the loss of Aksai Chin remains a contentious issue, with the region still at the heart of the ongoing India-China border dispute.

The declassified report offers critical lessons for India’s contemporary foreign policy and defence strategy. Nehru’s policy of accommodation, while rooted in a vision of peaceful coexistence, underestimated China’s expansionist ambitions and overestimated the efficacy of diplomacy in the face of military aggression. The failure to secure Aksai Chin in the 1950s had long-term consequences, contributing to the 1962 Sino-Indian War, in which India suffered a humiliating defeat, losing further territory and prestige.

Today, as India and China continue to grapple with border tensions—most recently in eastern Ladakh during the 2020 Galwan clash—the insights from this document are particularly relevant. India has since adopted a more assertive posture, bolstering its military presence along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and investing in infrastructure to counter Chinese incursions. However, the legacy of Nehru’s policies, including the prioritization of diplomacy over military preparedness, continues to influence India’s strategic calculus.

The declassified 1950-1959 summary reveals the complexities of Nehru’s China policy, highlighting a decade of missed opportunities and strategic misjudgments. While Nehru’s vision of friendship with China was idealistic, it failed to account for Beijing’s aggressive territorial ambitions, particularly in Aksai Chin. The document serves as a sobering reminder of the importance of balancing diplomacy with military readiness—a lesson India has since internalized as it navigates its fraught relationship with China in the 21st century. As India continues to build its defence capabilities and assert its regional influence, the echoes of the 1950s underscore the need for a pragmatic, forward-looking approach to national security.

NOTE: AFI is a proud outsourced content creator partner of IDRW.ORG. All content created by AFI is the sole property of AFI and is protected by copyright. AFI takes copyright infringement seriously and will pursue all legal options available to protect its content.