SOURCE: AFI

In recent years, the relationship between the Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA) and the Aeronautical Development Establishment (ADE) has seen increasing tension, particularly after the controversial shift of the Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle (UCAV) programme from ADA to ADE. This change, which has left many within the defense and aerospace sectors questioning its implications, has led to a souring of what was once a collaborative working dynamic between two pivotal organizations in India’s aerospace sector.

To understand the gravity of this shift, it’s essential to first grasp the roles and functions of ADA and ADE. ADA is the lead agency responsible for the development of advanced fighter aircraft and systems for the Indian Air Force (IAF). It is most notably recognized for its work on the Tejas light combat aircraft, one of India’s most significant homegrown aviation projects. ADA’s primary mandate is to integrate and oversee the design, development, and validation of next-generation aviation technologies.

On the other hand, ADE, an organization under the Defense Research and Development Organization (DRDO), is mainly tasked with the development of unmanned aerial systems (UAS), such as UAVs and UCAVs. ADE has been pivotal in the creation and evolution of various unmanned systems for the Indian defense sector, including the Nishant and the Rustom series of drones.

Historically, both ADA and ADE have worked in tandem to propel India’s aerospace capabilities. However, recent developments, particularly the shift of the UCAV programme, have strained their working relationship.

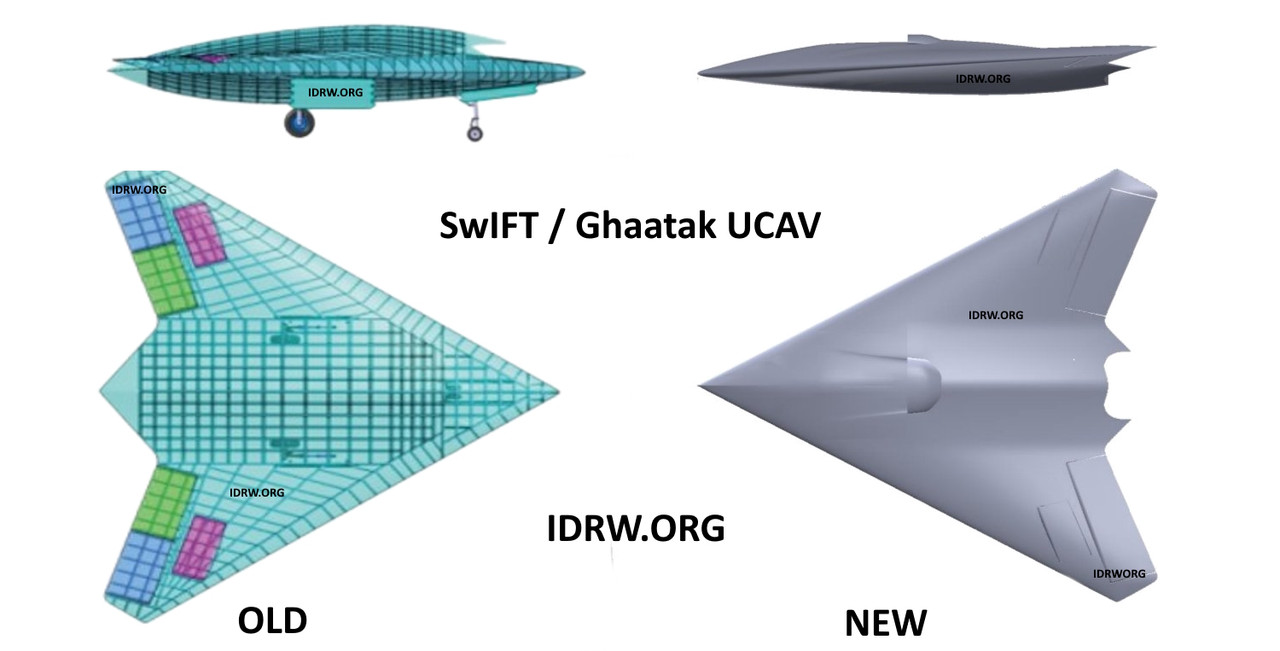

The decision to move the UCAV programme from ADA to ADE marks a significant turning point in the collaboration between these two agencies. The UCAV, which is expected to play a crucial role in enhancing India’s aerial warfare capabilities, was initially under ADA’s purview. This decision was in line with ADA’s expertise in manned and unmanned aircraft systems, especially given their experience in developing advanced fighter aircraft.

However, when the government made the decision to transfer the programme to ADE, it raised eyebrows and led to speculation about the underlying reasons for such a shift. The move has created an atmosphere of discontent within ADA, with officials expressing concerns about the implications for the future of the UCAV programme and their role in India’s aerospace development.

Several factors seem to have contributed to the transfer of the UCAV programme to ADE. One of the primary reasons cited is the focus and specialization of ADE in unmanned systems. While ADA has made remarkable progress in the development of manned aircraft, ADE has a more extensive history and expertise in unmanned aerial vehicles. The UCAV, being an unmanned system, might have seemed more naturally aligned with ADE’s capabilities.

Additionally, the growing importance of drones and unmanned aerial systems in modern warfare may have led the government to prioritize ADE’s involvement in such advanced projects. The rapid technological advancements in drone warfare and the need for a dedicated focus on these capabilities might have influenced this decision.

However, it is not only technical and strategic factors that have come into play. There are also underlying administrative and organizational concerns that have created a sense of discord. The shift has raised questions about decision-making processes within India’s defense establishments and has led to concerns over the long-term implications of this move on ADA’s morale and productivity.

The aftermath of the UCAV programme shift has not been smooth. ADA’s frustration with the decision is palpable, as many believe that the shift undermines their role and expertise in developing cutting-edge aviation technology. ADA’s personnel, who have dedicated years to mastering the intricacies of aircraft design and integration, now feel sidelined in a project that could have aligned with their experience in advanced aerospace development.

Moreover, there is concern within ADA that the change could affect future projects that involve the development of systems combining both manned and unmanned technologies. This could further erode the synergy between ADA and ADE, as the two organizations have traditionally worked together in areas such as fighter aircraft development and UAV integration.

For ADE, the new responsibility is both an opportunity and a challenge. Taking on the UCAV programme places the organization in the spotlight, but it also comes with its own set of challenges. Developing a sophisticated combat drone is an ambitious undertaking, and ADE will need to ensure that its resources, technological expertise, and leadership are up to the task. The pressure to deliver a successful UCAV may put a strain on the agency, especially as it continues to manage its other unmanned vehicle projects.