SOURCE: AFI

The Indian Army’s pursuit of modern Anti-Tank Guided Missiles (ATGMs) has hit a rocky patch, with two high-profile foreign systems—the Israeli Spike and the American Javelin—failing to impress in rigorous field trials. The Spike ATGM, procured in limited numbers since 2019, floundered during tests in the scorching Thar Desert, while the Javelin met a similar fate in the high-altitude terrain of Ladakh in September-October 2024.

These setbacks have ignited a firestorm among defence analysts, who are now questioning the Army’s procurement decisions—especially when locally developed ATGMs like the DRDO’s Man-Portable Anti-Tank Guided Missile (MPATGM) face years of exhaustive trials before induction. As the Army pushes forward with plans to acquire more foreign systems, the contrast between imported failures and indigenous rigor is raising eyebrows and fueling calls for a rethink.

The Indian Army’s tryst with the Spike ATGM began in 2014, when it selected the Israeli system over the Javelin in a $1 billion deal for 8,356 missiles and 321 launchers. Touted as a third- and fourth-generation fire-and-forget missile with a range of up to 4 km, the Spike was seen as a quick fix for the Army’s shortfall of over 44,000 ATGMs against its sanctioned strength of 81,000. However, the deal was repeatedly derailed—first canceled in 2017 in favor of the DRDO’s MPATGM, then revived in 2018 during Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu’s visit, only to be axed again in 2019 after trials exposed glaring flaws.

Reports indicate that during summer trials in the Thar Desert’s Pokhran Field Firing Range, the Spike’s sensors failed to reliably detect targets amid the extreme heat and dust—conditions typical of India’s western borders. A source familiar with the tests told DefenseWorld.net, “The missile failed in multiple areas… Sensors couldn’t identify the target,” casting doubt on its suitability for the Army’s operational needs. Despite this, the Army procured 240 Spike MR (Medium Range) missiles and 12 launchers in 2019 under emergency powers, followed by Spike LR (Long Range) variants in 2020 amid the Ladakh standoff with China. Analysts now question why a system that flunked trials was fast-tracked while indigenous options languished.

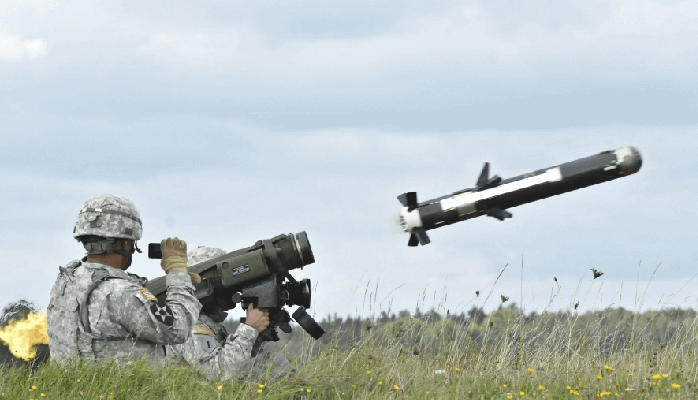

Fast forward to 2024, and the Army’s interest in the U.S.-made Javelin ATGM—an iconic fire-and-forget system with a 2.5-4 km range—has also hit turbulence. As part of negotiations for co-production under the U.S.-India Defence Technology and Trade Initiative (DTTI), the Javelin was tested alongside the Stryker infantry combat vehicle in Ladakh’s rugged, high-altitude terrain (13,000-18,000 feet) last September-October. The trials aimed to assess its performance in the thin air and extreme cold of the Line of Actual Control (LAC), where modern ATGMs are critical against Chinese armored threats.

The results, however, were underwhelming. Sources cited by The Hindu and Indian Defence Research Wing (IDRW) noted that the Javelin “did not meet expectations fully,” with its performance hampered by the “vintage” of the system provided—suggesting an older variant was tested rather than the latest iteration. The Army has since requested re-trials, but the initial failure has stoked skepticism. Posts on X captured the frustration: “Stryker+Javelin ATGM flunked in Ladakh last yr, and now Army calls for re-trials. Why chase imported scrap?” asked one user, reflecting a growing sentiment that foreign systems are being favored despite subpar results.

Contrast this with the journey of India’s homegrown ATGMs, notably the MPATGM, developed by the DRDO as a third-generation fire-and-forget system derived from the Nag missile. Since its first test in 2018, the MPATGM has undergone a grueling gauntlet of trials—over a dozen by 2024—across deserts, plains, and high altitudes, including a successful warhead penetration test at Pokhran in August 2024. With a 4 km range, a lightweight 14.5 kg design, and advanced imaging infrared (IIR) seekers, it matches or exceeds the capabilities of Spike and Javelin, yet remains in the “final user evaluation” phase, awaiting bulk orders.

The Nag ATGM, another indigenous offering, completed summer trials in 2019 and is ready for induction, boasting a 4 km range and jam-proof optical guidance. Similarly, the helicopter-launched Helina (Dhruvastra for the IAF) has aced tests since 2018, proving its 7 km range in Ladakh’s high altitudes. Yet, these systems face years of scrutiny—often spanning a decade—while foreign ATGMs with documented failures secure emergency procurements. “DRDO’s MPATGM has been tested to death for years, but Spike and Javelin fail once and still get a nod. What’s the logic?” tweeted a defence enthusiast, summing up the analysts’ ire.

Defence analysts are baffled by the Army’s persistence with Spike and Javelin despite their trial flops. The Spike’s desert failure and partial induction underline a pattern of accepting foreign systems as “stop-gap” measures, even when they underperform in India’s diverse terrains—hot deserts, freezing mountains, and humid coasts. The Javelin’s Ladakh setback, coupled with U.S. reluctance to transfer critical technology in earlier talks (a sticking point since 2010), further muddies the case for co-production.

Meanwhile, indigenous ATGMs endure a far stricter gauntlet. The MPATGM, for instance, was delayed by the Army’s shifting weight requirements—initially deemed too heavy at 14.5 kg compared to Javelin’s 11.8 kg—despite matching global benchmarks. Posts on X highlight the disparity: “Indian ATGMs go through multiple trials for years, but Army agrees to procure Spike and Javelin after they flunk. Billions spent on desi tech, yet we buy foreign rejects,” wrote one user. Another analyst pointed out, “Nag, Helina, MPATGM—proven in Thar and Ladakh—still wait, while failed imports get fast-tracked. It’s beyond comprehension.”

The Army’s rationale—urgent operational needs, especially post-Galwan in 2020—holds some weight. With a shortfall of modern ATGMs and ageing Milan and Konkurs systems (second-generation, wire-guided relics), emergency buys of Spike addressed immediate gaps along the LAC. Yet, critics argue this short-term fix undermines long-term self-reliance. The MoD’s October 2024 Request for Information (RFI) for 1,500 ATGMs under the Buy (Indian-IDDM) category suggests a pivot toward indigenous options—but only after years of flirting with foreign failures.

NOTE: AFI is a proud outsourced content creator partner of IDRW.ORG. All content created by AFI is the sole property of AFI and is protected by copyright. AFI takes copyright infringement seriously and will pursue all legal options available to protect its content.