SOURCE: AFI

In a dramatic escalation of regional tensions, India’s withdrawal from the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in 2025 has triggered a wave of provocative rhetoric in China, particularly on social media platforms. Some Chinese netizens have called for damming the Brahmaputra River—known in China as the Yarlung Zangbo—to choke off water supplies to downstream India. This inflammatory narrative, though not officially endorsed by Beijing, underscores the fragility of transboundary water governance in South Asia and the potential for water to become a geopolitical weapon.

The IWT, brokered by the World Bank in 1960, has long governed the sharing of the Indus River system’s waters between India and Pakistan. India’s decision to withdraw from the treaty, citing national security concerns and dissatisfaction with Pakistan’s compliance, has sent shockwaves through the region. The move has not only strained India-Pakistan relations but also prompted neighboring China to reassess its own strategic position as an upstream power controlling critical water resources.

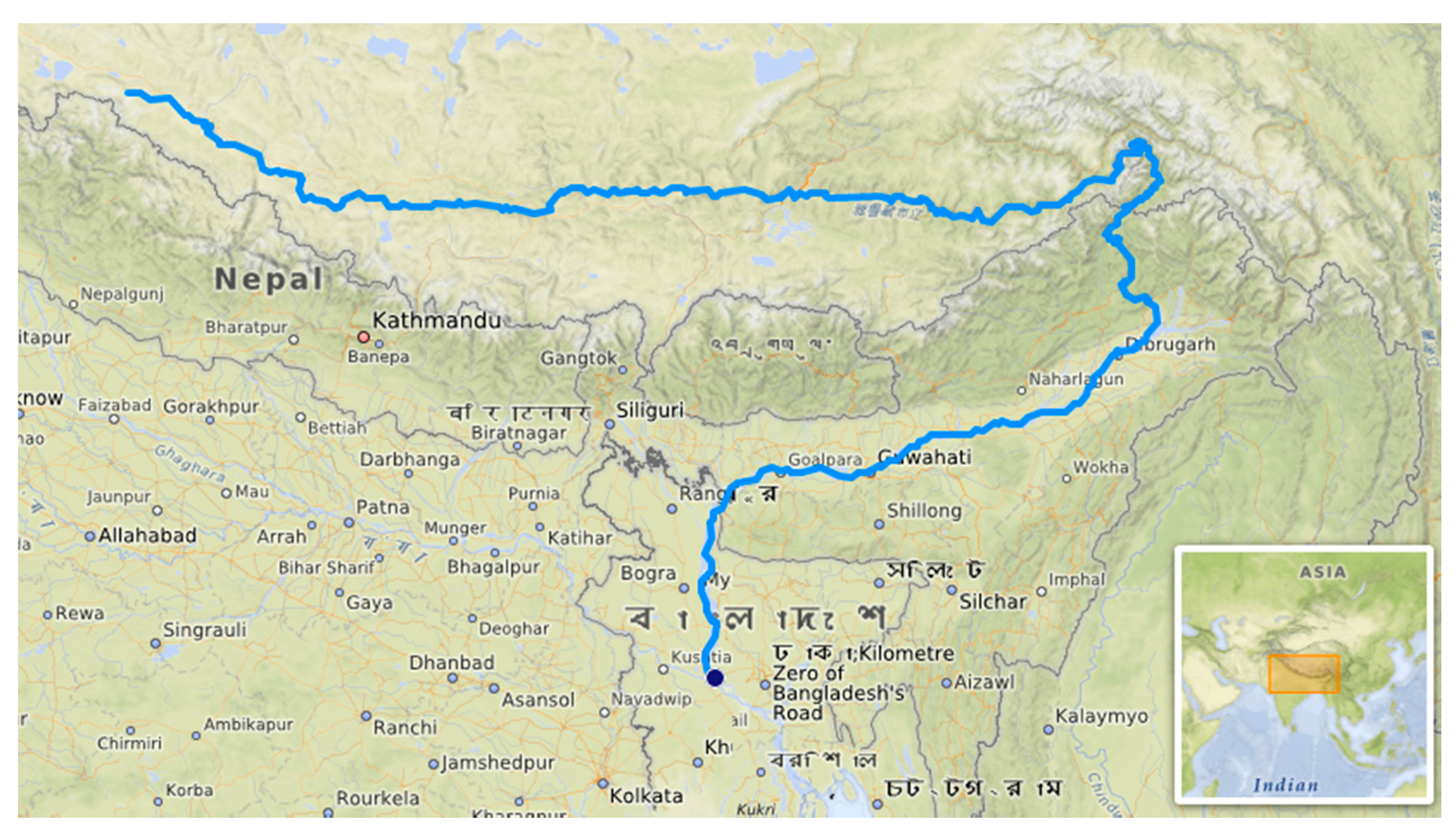

The Brahmaputra, originating in Tibet and flowing through India and Bangladesh before emptying into the Bay of Bengal, is a lifeline for millions. In India, it supports agriculture, hydropower, and livelihoods, particularly in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. Any disruption to its flow could have catastrophic consequences, making the river a potential flashpoint in India-China relations.

Following India’s IWT withdrawal, posts on Chinese platforms like Weibo and Douyin began circulating calls to dam the Yarlung Zangbo as a retaliatory measure. Users argued that India, as a downstream nation, should face consequences for destabilizing regional water agreements. “If India can abandon treaties, why should China share its water?” one widely shared post read. Another user suggested that a mega-dam could “teach India a lesson” by controlling the Brahmaputra’s flow.

These sentiments, while not reflective of official policy, have gained traction amid rising nationalist fervor in China. The idea of weaponizing water resonates with some who view India’s IWT exit as a challenge to regional stability. However, such actions, if pursued, would violate international norms, including the principle of “no harm” in transboundary water management, and could escalate tensions with India, already strained over border disputes and geopolitical rivalry.

China has long eyed the Yarlung Zangbo for its hydropower potential. Plans for mega-dams in Tibet, including a proposed project in the river’s Great Bend, have raised concerns in India and Bangladesh for years. These dams could generate significant electricity for China but also give Beijing unprecedented control over the Brahmaputra’s flow. While China has maintained that its projects are for domestic energy needs and not intended to harm downstream nations, the lack of transparency and data-sharing has fueled distrust.

The social media calls for damming the river have reignited fears in India that China could use its upstream position strategically. Experts warn that even temporary reductions in flow—whether for hydropower storage or as a political signal—could disrupt agriculture, fisheries, and flood patterns in India’s northeast. In Bangladesh, which relies on the Brahmaputra for 6% of its freshwater, the impacts would be equally severe.

India has yet to officially respond to the social media rhetoric, but New Delhi is likely to view these calls as a provocative signal. The Indian government has previously expressed concerns about China’s dam-building activities, urging Beijing to share data on river flows and project plans. India’s own hydropower projects on the Brahmaputra, particularly in Arunachal Pradesh, are partly seen as a counterbalance to China’s upstream dominance.

The rhetoric also complicates India’s relations with Bangladesh, which has sought assurances from both New Delhi and Beijing on maintaining the Brahmaputra’s flow. Any move by China to restrict water could strain India-Bangladesh ties, as Dhaka might perceive India’s IWT withdrawal as a catalyst for regional water conflicts.

The Brahmaputra controversy highlights the growing role of water in geopolitical rivalries. South Asia, home to some of the world’s most critical river systems, faces increasing pressure from population growth, climate change, and competing national interests. The collapse of the IWT has already raised questions about the durability of other water-sharing agreements, and China’s upstream control of rivers like the Brahmaputra and Mekong gives it significant leverage.

International law offers limited recourse. The 1997 UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, which emphasizes equitable use and cooperation, has not been ratified by China or India. Without binding frameworks, unilateral actions—whether India’s IWT withdrawal or China’s potential damming—risk escalating into broader conflicts.

NOTE: AFI is a proud outsourced content creator partner of IDRW.ORG. All content created by AFI is the sole property of AFI and is protected by copyright. AFI takes copyright infringement seriously and will pursue all legal options available to protect its content.